The JFK Assassination at 60: The Public Knows the Truth - Why Won’t the Media Report It?

By David Talbot, columnist, The Kennedy Beacon

By David Talbot, columnist, The Kennedy Beacon

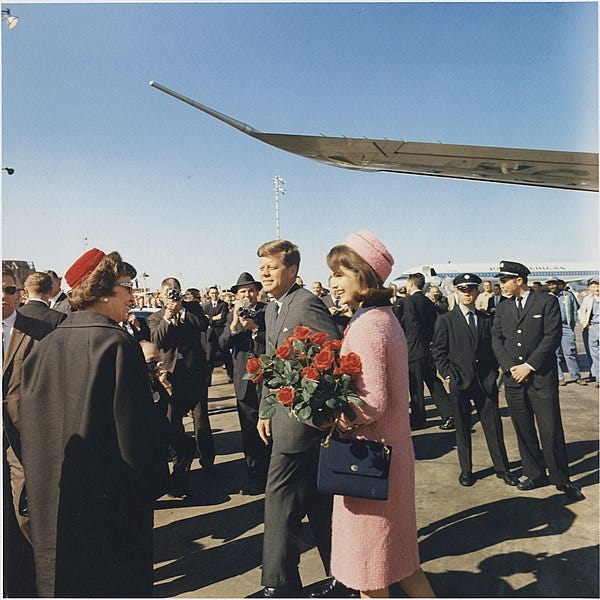

The official story of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination is finally falling apart, nearly 60 years after gunfire erupted in Dallas’s Dealey Plaza. The mother of all conspiracies turns out to be true, according to a media barrage this anniversary season, including a new documentary, TV special, podcast, book, scholarly conference and news revelations.

That “lone gunman” version always stretched credulity, relying on a “magic bullet” that allegedly caused seven entry and exit wounds in President Kennedy and Texas Governor John Connally before emerging in nearly pristine condition on a hospital stretcher. In his recent book, The Final Witness, former Secret Service agent Paul Landis asserts that he found the bullet on the back seat of the presidential limousine after it only slightly penetrated the back of the president. In other words, there was nothing magic about the bullet at all.

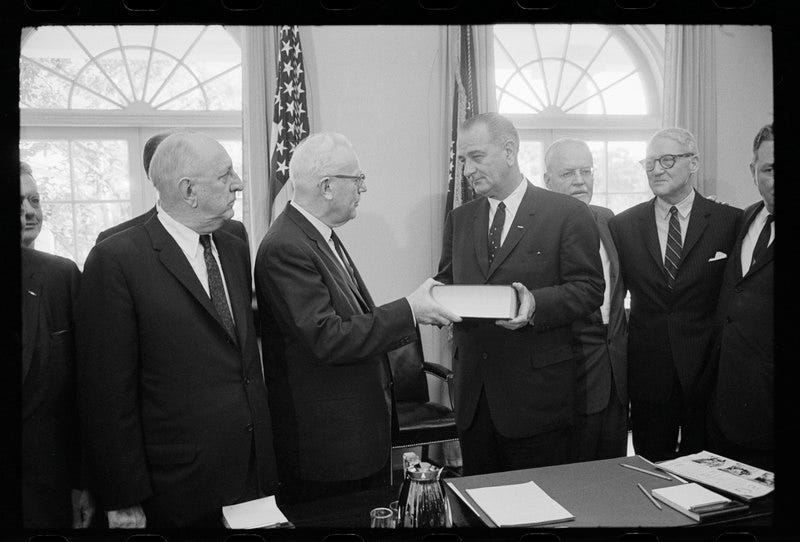

Despite the shaky case for a single assassin, this story was promoted by government authorities as soon as Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested for the shocking crime on November 22, 1963. And it was embraced by the Warren Commission, the inquiry panel of distinguished public figures appointed by President Lyndon Johnson, when it released its report the following year.

The press, too, eagerly applauded the Warren Report, with The Washington Post reporter Robert J. Donovan praising it as a “masterpiece of its kind” and Anthony Lewis of The New York Times predicting the report would “completely explode” conspiracy theorists like Mark Lane, author of the skeptical Rush to Judgement.

Privately, prominent people like French President Charles de Gaulle and Robert F. Kennedy, President Kennedy’s brother and the attorney general, dismissed the Warren Report as a publicity exercise – or “baloney,” in de Gaulle’s contemptuous estimation, designed to head off a potential “civil war.”

“Better an injustice than disorder,” the French president said of Oswald’s silencing by triggerman Jack Ruby. “In order to not risk unleashing riots in the United States.”

Robert Kennedy and his grieving sister-in-law, Jacqueline Kennedy, were worried that President Kennedy’s assassination could spark something even more catastrophic. To avoid a nuclear confrontation with the Soviet Union, a week after the president was killed, the Kennedys dispatched close family friend and painter William Walton, who was due to meet with Russian artists as part of an exchange mission, to confer secretly at a Moscow restaurant with Georgi Bolshakov, a Soviet intelligence agent. The two Kennedy brothers had come to trust Bolshakov — whom Newsweek called “the Russian New Frontiersman” — as a back-channel to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev at critical times like the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Over their meal — which took place during the height of the Cold War, when suspicions between the superpowers were high — Walton passed a remarkable message to Bolshakov. Bobby and Jackie Kennedy believed that JFK was the victim of a high-level domestic conspiracy, not a Communist plot, as FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had told them. Walton also told the stunned Soviet agent that RFK planned to pursue a political career and he would resume his brother’s policy of détente with Moscow if he made it to the White House.

Bobby Kennedy — who was elected to the Senate from New York in 1964 and ran for president in 1968, before he too was cut down by an assassin’s bullet – was the first prominent JFK conspiracy theorist. “With that amazing computer brain of his, he put it all together on the afternoon of November 22,” RFK’s friend, journalist Jack Newfield, told me for my 2007 book, Brothers: The Hidden History of the Kennedy Years, which chronicled Bobby’s confidential search for the truth about Dallas. RFK, who was his brother’s principal emissary to the dark side of power, suspected that the plot against JFK grew out of the CIA’s unsavory operation against Cuba, which employed gangsters, anti-Castro militants and other ruthless characters.

Over the years, other leading men and women of the time came to share Bobby Kennedy’s suspicions about the JFK assassination, including philosopher Bertrand Russell; theologian Thomas Merton; political satirist Mort Sahl; musician David Crosby of the Byrds; poet Allen Ginsberg; and writers Robert Graves, Katherine Anne Porter, Ray Bradbury and Paddy Chayevsky. Terry Southern — who co-wrote the screenplay for Dr. Strangelove, which conveyed the darkly macabre humor of the nuclear doomsday era — bitterly denounced the official version of President Kennedy’s assassination in a survey mailed to over 300 prominent citizens in the 1960s. “The absurdity of the Warren Report is patent and overwhelming,” Southern wrote at the bottom of the survey. “One has only to browse through any of the 26 volumes to know at once what a complete farce, charade, and incredible piece of bullshit it is.”

At least three members of the Warren Commission itself — Senators Richard Russell and John Sherman Cooper as well as Representative Hale Boggs — did not buy their own report’s lone gunman conclusion. But the persuasive Lyndon Johnson and devious commission chief counsel J. Lee Rankin herded the dissenters into unanimity.

By the 1970s, following the Vietnam War debacle and the Watergate revelations, Senator Frank Church established some supervision over the CIA, at least for a time. In late 1975, as the Church investigation was winding down, Senator Richard Schweiker, a moderate Republican from Pennsylvania, persuaded Church to let him set up a subcommittee on the JFK assassination. After his brief but intense investigation, he concluded “Oswald had intelligence connections. Everywhere you look with him, there are fingerprints of intelligence.”

That spirit of inquiry led to the formation of the House Select Committee on Assassinations, which found in its 1979 report that President Kennedy was indeed the victim of a “conspiracy,” a historic break from the government’s lone gunman dogma. But the HSCA’s conclusion was vague about the likely culprits, leaving the CIA off the hook, and it was overshadowed by the earlier Warren Report.

In 2001, journalist Jefferson Morley informed G. Robert Blakey, the House assassination panel’s chief counsel, that his investigation had been sabotaged by its CIA liaison, an agency official named George Joannides, who turned out to have a shadowy connection to the Kennedy case. “Joannides’s behavior was criminal,” said the furious Blakey, who is now an emeritus professor at the University of Notre Dame’s law school. The revelation about Joannides turned Blakey’s focus more on the CIA and its web of contractors.

In 2019, Blakey and other prominent JFK experts — including Dr. Robert McClelland, one of the surgeons who worked on the mortally wounded president at Dallas’s Parkland Memorial Hospital — signed a public statement that I helped arrange. It concluded that “the conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy was organized at high levels of the U.S. power structure, and was implemented by top elements of the U.S. national security apparatus using, among others, figures in the criminal underworld to help carry out the crime and cover-up.”

Polls since the JFK assassination show that the American public consistently views the lone gunman story with skepticism. While the Warren Report convinced most Americans, by the 1970s there was growing suspicion that elements of the government itself were involved in the plot, as revealed in a recent Gallup survey that found a solid 65 percent of adult Americans believe that JFK was the victim of a conspiracy, with most of the skeptics pointing to the federal government, and specifically the CIA, as the likely culprits.

Strangely, one of the few holdouts for the official version of the JFK assassination is the mainstream media. But even there, support for the Warren Report has grown shaky. During my research for Brothers, 60 Minutes creator Don Hewitt and former Washington Post executive editor Ben Bradlee — two of the grand men of U.S. investigative journalism (both now deceased) — told me of their own dark suspicions about Dallas. “I just never believed (the official story) for one second,” Hewitt told me in 2005, the year after he stepped down at 60 Minutes. He suspected “disgruntled CIA types” were responsible for JFK’s murder, but he claimed his investigative team could never nail it down.

I asked Bradlee in 2004 why The Washington Post didn’t devote investigative resources to the JFK murder story. After all, Bradlee wrote a warm 1975 memoir of his companionship with the president, Conversations with Kennedy. Bradlee initially sidestepped the question. But by then occupying an emeritus position at the newspaper, he leveled with me. It would have damaged his budding journalism career, he admitted, if he had explored who killed his friend. He feared “that I would be discredited for taking the (Post newsroom) down that path.”

The New York Times, too, has grown less confident in the Warren Report over the years. By 1992, even Times reporter and columnist Anthony Lewis evolved from scourging the report’s critics to a less certain position. “Maybe with all that happened, Vietnam and Watergate, today’s reporters would have come to it with more resistance,” he told the Village Voice that year.

In recent months, Peter Baker, the Times’s chief White House correspondent, has covered two important developments in the Kennedy case, the Landis revelation about the magic bullet and the discovery that the CIA was secretly reading Oswald’s mail before the Kennedy assassination. This was an eye-popping story because the agency had long claimed that Oswald was off its radar before the assassination — a dubious assertion about a former Marine who defected to the Soviet Union, threatening to reveal military secrets, and then returned to this country with a Russian wife. Baker is clearly open to new information about the JFK case.

Despite this flirtation with the truth, The New York Times and the rest of the mainstream media remain largely wedded to the official version of Dallas. Last week, I was asked by a Times opinion editor to write a JFK assassination op-ed, but the newspaper rejected my measured article (a version of what you’re reading). “The piece is rich and fascinating,” the editor emailed me, “but I don't think I can move forward with it. The fascinating mobius strip of truth and conspiracy is very tricky for Times Opinion.”

Big media is not the only barrier to the truth about JFK. Despite the public’s ongoing suspicions about the Kennedy case, which led to the febrile conspiracy culture in this country, the government continues to stonewall. In direct violation of the 1992 JFK Records Collection Act, which sought to release all government documents related to the Kennedy assassination, President Trump and Biden repeatedly delayed declassification of nearly 4,000 documents, most of them stubbornly held by the CIA. After nearly six decades, when all the key players are dead, there is no “national security” justification for this government secrecy. By law, this historical material belongs in the hands of the press and public now.

I am among those researchers who’ve sued the government for access to these records. While working on The Devil’s Chessboard, my 2015 book about Cold War-era CIA Director Allen Dulles, I filed a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit against the CIA and State Department for the passport and travel records of William Harvey, the spy agency’s assassinations chief. Before the JFK assassination, Harvey — an impassioned Kennedy opponent — was spotted on a plane to Dallas by his deputy, F. Mark Wyatt, even though Harvey was stationed in Rome at the time. Wyatt later concluded that Harvey played a role in the assassination. But the government agencies successfully blocked my legal effort. (Dulles, who has also been implicated in the plot by me and other JFK researchers, played an active role on the Warren Commission even though President Kennedy fired him from the CIA after its disastrous 1961 invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs.)

And yet, as we approach the 60th milestone of the JFK assassination, we are finally shaking free the truth about this clandestine case. Amid the avalanche of JFK memorials this season, there are some worth tuning into.

Last week, Paramount+ streamed JFK: What the Doctors Saw, the blunt eyewitness testimony of Dr. McClelland and several other members of the surgical team that worked on JFK at the Dallas hospital and saw with their own eyes that he was struck by bullets from the front and rear. In other words, clear evidence of a conspiracy.

Also, Hollywood actor and filmmaker Rob Reiner teamed up with longtime Kennedy assassination author Dick Russell to produce the podcast Who Killed JFK? And on November 22, documentary filmmakers John Kirby and Libby Handros will release the opening episode of Four Died Trying, their film series on the major assassinations of the 1960s. This follows the 2021 documentary JFK Revisited: Through the Looking Glass by director Oliver Stone, the man whose 1991 movie JFK compelled Congress to pass the JFK Records Act and inspired a new generation of Warren Report critics.

From November 15 through 17, the Cyril H. Wecht Institute of Forensic Science and Law at Pittsburgh’s Duquesne University sponsored a scholarly conference titled “The JFK Assassination at 60,” featuring speakers like former Secret Service agent Landis, presidential historian Barbara Perry, retired Army intelligence officer and author John Newman, Dealey Plaza forensics experts Josiah Thompson and Dr. Gary Aguilar, lawyer and Kennedy authority Daniel Alcorn and me.

Meanwhile, journalist Morley, who’s been working the Kennedy beat for over 30 years and now edits a Substack blog called JFK Facts, continues to report on the historic events in Dallas as a hot news story, working closely with Rex Bradford at the Mary Ferrell Foundation — the leading electronic repository of Kennedy records — to break big headlines.

As I’ve long said, quoting the musician Leonard Cohen, there’s a crack in everything, that is how the light gets in. Nowadays, it seems like the light is pouring through.

David Talbot is the author of The New York Times bestsellers The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA and the Rise of America’s Secret Government and Brothers: The Hidden History of the Kennedy Years.

Remarkable piece. Thank you for this. The implications are enormous. I'm also disillusioned with the legacy media. At every turn, they decide to do the wrong thing.

People claim the media was more trustworthy in the past. Well, no, I don't think so. To me it seems we simply gained life experience (and the Internet) and realized that much of the "news" we were being fed it actually propaganda. We've been "lied" to for a very long time (my entire lifetime).